Some companies launching employee innovation programs will inevitably find the going tough. They'll launch their innovation initiative with great fanfare. They'll give themselves the powerful advantage of using a campaign-based innovation approach. But will be disappointed when the employee ideas they see fail to drive the value they were seeking.

Why? As philosopher John Dewey noted:

"A problem well put is half-solved".

The mistake a number of these organizations will run into is that the problem they're trying to solve is not well put. Not the grammar of the question, but the fundamentals of what is asked, and how it is asked. With the predictable downstream effects of less-than-adequate ideas.

With that in mind, let's look at three mistakes that mean a problem has not been well put from the employees' perspective. Understand these mistakes, and you're closer to uncovering the novel, high-potential ideas you're seeking.

Mistake #1: The Overask

Casting a question to a community is a wonderful form of engagement. You've got the attention of many people. You're going to receive an interesting mix of responses. A great way to crack open a tough problem.

But, since you've got their attention, maybe they can provide some answers for some additional areas. That way you don't have to ask later. This is The Overask. Below is a modified version of an actual question that was asked of employees:

How might we become more competitive? Think in terms of new revenue sources, increased efficiencies, non-value-added work, margin enhancements, etc.

Revenue. Operational efficiency. Bureaucracy. Margins. All in one question. It even includes "etc", which is essentially asking for everything but...

This is a textbook case of the "overask". Issues that arise with this question:

- Ideas will be all over the board, with employees assuming conflicting definitions for what "more competitive" means.

- The basis for evaluating the different types of ideas will vary greatly (e.g. new revenue opportunities vs. cutting bureaucracy). How to effectively assess the different ideas?

- The ability of the crowd to go deeper into a specific area is hindered by the breadth of submissions. It's hard to build on ideas addressing such widely divergent topics.

Mistake #2: Too specific! Not specific enough!

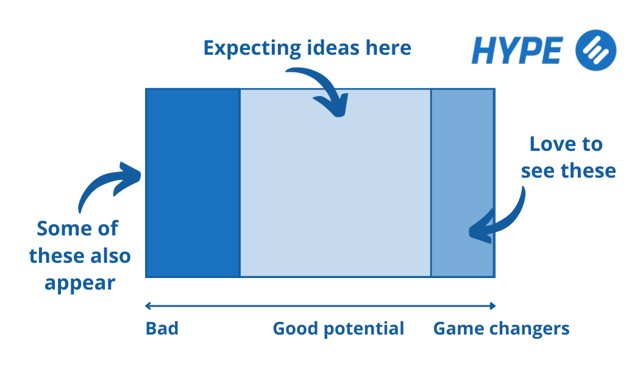

In asking a question, be mindful of the responses you're seeking. At the outset, expectations for a given campaign look something like this:

Those are the expectations, but then there's the reality. The degree of specificity in the question will affect the width of those outcomes. In other words, the way you ask the campaign question impacts the shape of the ideas you will see.

There are times when a very specific sort of idea is needed. For example, you'd ask a question such as: How can we reduce the amount of fuel used by our trucking fleet while they're dropping off and picking up goods at our warehouses? The effect of that is to narrow the range of outcomes in questions due to its specificity.

On the other hand, it's possible to ask a question that can elicit a wide range of responses. This is not the Overask, where too many topics are asked at once. Rather, it's focused on a topic but with a deliberate vagueness to open the aperture for ideas. For instance, one could ask: How can we change our distribution processes to better deliver goods? The effect is to expand the range of ideas submitted. Because of the blue-sky thinking that comes with asking such a wide-open question, the outcomes expand.

The mistake organizations can make is to have a mismatch in expectations. You were expecting workable ideas with good, positive potential, but you got a whole heap of crazy ideas that don't match expectations. And you weren't ready to handle some of the out-there ideas that could be game-changers.

Or you were seeking a range of ideas that reflected some blue-sky thinking. But you were so specific in your question that people didn't realize that was expected. You're surprised at the pedestrian nature of the ideas.

Match the "ask" with what you're ready for.

Mistake #3: Who?

When asking employees for ideas, it matters who is making the request. Why? Because employees will make an instant judgment about the legitimacy of the campaign based on who sends the email.

Let's imagine that the two emails are sent. They each announce the same innovation campaign. But there's a difference in senders.

The first email makes the effort appear to be an out-of-the-mainstream project. By a group that people don't really know well. And given the group's position, the best it can do is forward the ideas to relevant executives for their consideration. Why would an employee spend time investing effort in this campaign?

The second email comes from a senior executive that employees know. This executive speaks with authority, and everyone understands that the effort is real. He is able to state the sort of ideas being sought, and back the effort up with a real plan for action. Both the executive's presence and the specifics for how ideas will be considered and developed significantly increase the legitimacy of the effort. It will be worth the employees' time to participate.

Avoid the mistake of not considering "Who" is presenting the idea campaign, and don't underestimate the effect that will have on participation.

Final Thoughts

To sum up, starting programs for employee innovation can be tricky. Sometimes, despite trying hard, the ideas from employees don't bring the expected results.

The main problem is often how we ask the question. Here are three common mistakes: asking too much, being too specific or not specific enough, and not having the right person ask.

Fixing these mistakes can bring great new ideas. Avoiding these issues helps us ask better questions and gets us closer to finding awesome solutions from employees. So, let's learn from these mistakes and make our innovation efforts even better!

.jpg?width=558&height=372&name=charlesdeluvio-Lks7vei-eAg-unsplash%20(1).jpg)