Besides its recurring presence in aspirational (business) magazine story titles, the not-invented-here syndrome (NIH) - a close relative of the “let’s-reinvent-the-wheel” condition as this witty opinion article suggests, and of the classic “inventor myopia” as explained in Chapter 6 of Conquering Innovation Fatigue - also happens to be one of the most cited constructs in knowledge transfer literature.

Is this surprising? Hardly. As more organizations (large and small) struggle to make sense of, and ultimately leverage, the benefits of open innovation (i.e. seeking the delicate balance between “importing” and “exporting” know-how to sustain a competitive edge) the NIH syndrome, or a negative attitude towards knowledge (ideas, technologies) derived from an external source surfaces as a major (psychological) hurdle.

To illustrate, I ask you this:

Do you or your business leaders insist on justifying “home-grown” innovation when far more promising options lie beyond the boundaries of the firm?

Transfer and development costs held equal, of course. If the answer is a resounding YES, and if not all the fortune tellers in the industry work for you, you will likely find the discussion on NIH syndrome, at its core a decision-making bias, educative. In as follows, I invite you to delve into the latest (and most comprehensive) academic research on the phenomenon, circling the conclusions most relevant to you.

(image source: http://www.toonpool.com/user/4318/files/invention_1475525.jpg)

For the purpose of our exercise, I have leafed through Opening the Black Box of "Not-Invented-Here": Attitudes, Decision Biases, and Behavioral Consequences by David Antons and Frank T. Piller of RWTH Aachen University so you don’t have to. Here are some findings from their wonderfully documented work.

NIH: its causes and consequences

It probably does not take a rigorous scientific demonstration to convince you that organizational inertia and structural rigidities challenge the transfer and utilization of outside knowledge on the level of the organization. In fact, previous research has pointed to specific concepts, including representativeness, anchoring, availability, escalating commitment and the endowment effect. Within this club of economically damaging biases, NIH is by far the most widely cited reason for rejected or underutilized knowledge in the context of innovation. As the authors note:

"When NIH hinders the reception of knowledge, negative consequences are likely to occur."

Case-in-point: Apple Computer in the 1990s, when managers rejected good external ideas and lived in their own “reality distortion field”. The attitude is also common today among advocates of design-driven innovation – when the innovation in meanings defies everything else.

Finally, but not less importantly, NIH differs from organizational culture in that NIH is caused by individual attitudes and their functions as opposed to being a context.

Key features of NIH

The NIH syndrome has two key features: (1) it emerges as a result of boundaries that knowledge is required to bridge when transferred between two entities (for example, the knowledge about fish oils traveling from Ocean Nutrition Canada to Unilever in the process of creating the Becel Omega-3 Plus margarine); (2) it involves an irrational devaluation or rejection of this external knowledge by an individual (once again, the “reality distortion field” at Apple).

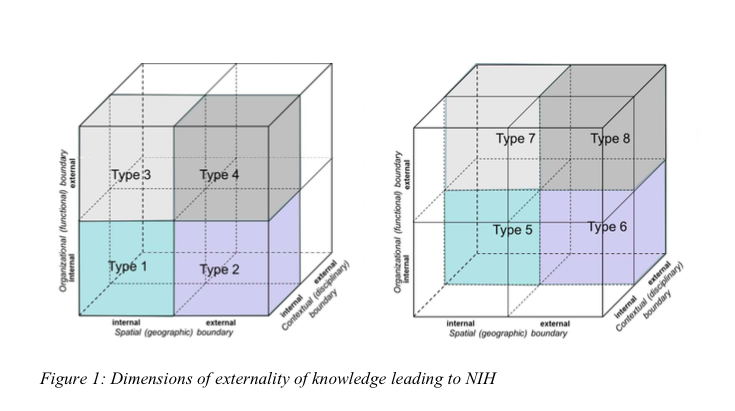

In terms of boundaries, knowledge (in any shape or form) can be external with regard to:

- its (disciplinary) context and

- its source (organizational/ functional boundaries and spatial/ geographic boundaries)

Hence, a 3D model depicting the dimensions of externality of knowledge leading to NIH.

(image source: Antons & Piller, 2015, published in: Academy of Management Perspectives)

The only type of knowledge transfer that is truly internal (i.e. internal along all 3 dimensions) and consequently not influenced by NIH is Type 1. Antons and Piller’s example is as follows: a team member transfers knowledge (e.g. sends a memo) to another team member located in the same geographical location; the two colleagues share the same educational background and the background itself is the same as the discipline from which the knowledge is transferred. Here is an additional example (from yours truly) to illustrate the rest: imagine two food scientists at Novozyomes Denmark sitting together one afternoon, sharing information about a new type of enzyme that will prevent special cheeses from melting excessively in customers’ ovens (again, Type 1 – so far, so good). If the scientist would be discussing matters with the head of R&D however, the transfer would become a Type 3 and NIH could potentially creep in. Similarly, if the Danish scientist would be Skyping with his peer in China, the transfer would become Type 2. Finally, if the head of R&D were situated in a remote location and were unable to follow the conversation clearly, this would represent evidence of a Type 4.

Also interesting & relevant for the discussion on the causes of the NIH syndrome is the disciplinary boundary. For instance, two team members from the same location but with different backgrounds result in Type 5. Yes, I’m referring to Marketing vs. Logistics, Manufacturing vs. R&D, Sales vs. HRM. Generally speaking, disconnected knowledge silos and the growing necessity to integrate information from different domains tend to take a serious toll in terms of wasted time and resources. Hence, the most dreaded forms of NIH are in fact Types 3 and 4 as well as Types 7 and 8. Knowledge is indeed most frequently rejected when it stems from a different function or source (firm).

Things have never been this nuanced, have they?

But wait, there is more.

In addition to knowledge externality (along the three dimensions explained above), the second element characterizing NIH is an irrational rejection of knowledge. (Slightly off-topic: Here is a nice piece on the bias against creativity)

The classic example is that of ideas for product/ service/ business model improvement from customers which some developers deliberately dismiss or ignore even if comes in the shape of a technically feasible suggestion. (More, but not most. Starwood is a nice exception!)

Why? For fear of increased workload or additional iterations of course.

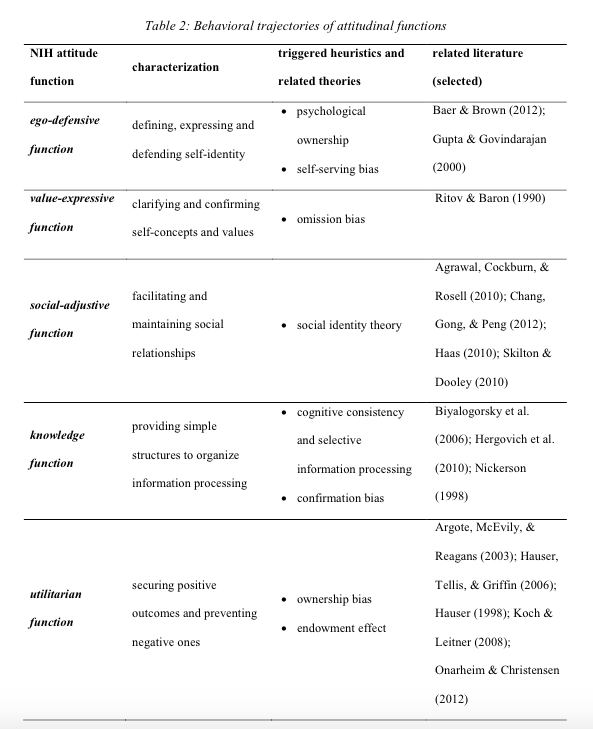

According to Antons and Piller, the bias underlying NIH syndrome can be explained through the lens of attitudes (NB: attitudes guide decision-making!) and their five major functions: ego-defensive function (maintain self-worth), value-expressive function (affirm a person’s central values), social-adjustive function (provide identity), knowledge function (help organize complex environments) and utilitarian function (help evaluate an object’s use).

A detailed description can be found in the table below. For example, some authors argue that an ego-defence mechanism may underlie NIH (some specialists obviously think of themselves as the single most capable persons to resolve a problem), while other authors argue that in the context of NIH the knowledge function of an attitude can lead to the so-called confirmation bias (specialists prefer – and even positively review - ideas that are similar to the prevailing norms).

(image source: Antons & Piller, 2015, published in: Academy of Management Perspectives)

Measuring and offsetting NIH

As we have seen, there are many aspects to be considered when tackling NIH and it’s not always clear where to start. Much like with any organizational problem, however, what does not get measured does not get managed. And you will want to manage this one because it hinders open innovation.

So how do we go about measuring the elusive NIH problem? Digging again through management literature will sadly be of little help. To date, only very few studies have provided direct measures of NIH and most of them have included standardized questionnaires about the utilization of external knowledge sources, collaboration with outsiders or trust in internally or externally developed technologies. As your intuition rightfully tells you, asking people directly about their attitudes will not do the trick. Enter: frequent biases. What about indirect measures then? Things like reaction times, sentence completion or picture classification? Yes, those might do a better job.

But if you really want a better understanding of NIH, and consequently better practice, here is a simple checklist to get you started:

- acknowledge that NIH exists (i.e. use the 8 Types and be on the lookout for irrational rejections);

- assess its current impact on your open innovation effort (i.e. how many opportunities have you missed?);

- build explicit incentives to overcome NIH (i.e. reward programs);

- engage outside people and organizations in the strategy and evaluation phases to receive fresh perspectives on your projects (i.e. independent advisory board anyone?).

Follow the prescription and your sub-optimal decision-making will be improved in no time.

Shifting from the restrictive “not-invented-here” to the all-empowering “proudly found elsewhere” is an inherently good move. Take DSM’s, a Dutch-based multinational life sciences and materials sciences company, word for it:

Related posts...