This is the fifth blog post in HYPE’s series on the most often-asked questions about strategic foresight. While the fourth post provided insights on where and how to identify industry trends, this post offers a step-by-step process for scenario planning to prep your organization for the future.

When trying to look ahead, we often run into two dilemmas. We either start to think and speak of the future in the singular, leading us to become narrow-minded, for example, in decision-making; or worse, we feel unable to see beyond the present at all, leaving us with confusion, hopelessness, and inaction. The good news is there are always alternatives – multiple futures which we can imagine, foresee, and bring to life, which is where scenario planning comes in.

A tool that can help transform a foggy future into a clearer landscape is called a scenario method. A scenario describes a possible future situation that develops from a chain of actions or drivers. Thus, the method produces narratives and simulations of possible futures. However, it does not predict. Rather, the method aims to create scenarios that could likely happen, are internally consistent in their logic or combinations of logic and can be used as tools for decision-making. Scenario planning often stretches our thinking and opens our eyes to new opportunities and hidden risks. Ultimately, some scenarios might be determined more plausible or even probable or preferred.

Here are the six steps to take when scenario planning.

Step 1: Identify and explore uncertainties

Many changes are outside of our control. In scenario work, these changes are called uncertainties: developments or changes lacking sufficient clarity in direction and speed, and which we need to explore in more detail. For example, the COVID-19 pandemic brings about the following uncertainties: How long will this pandemic last? Will this or some other pandemic reoccur? Most of us would answer these questions by stating, "I don’t know."

This is also the case with many other uncertainties. Before answering those kinds of questions, we first need to scope what “future of” we want to learn about and why, and understand what kind of uncertainties would be relevant to explore.

One way of identifying uncertainties is to look at the 11 sources of macro change, which include wealth distribution, education, infrastructure, government, geopolitics, economy, public health, demographics, environment, media and telecommunications, and technology.

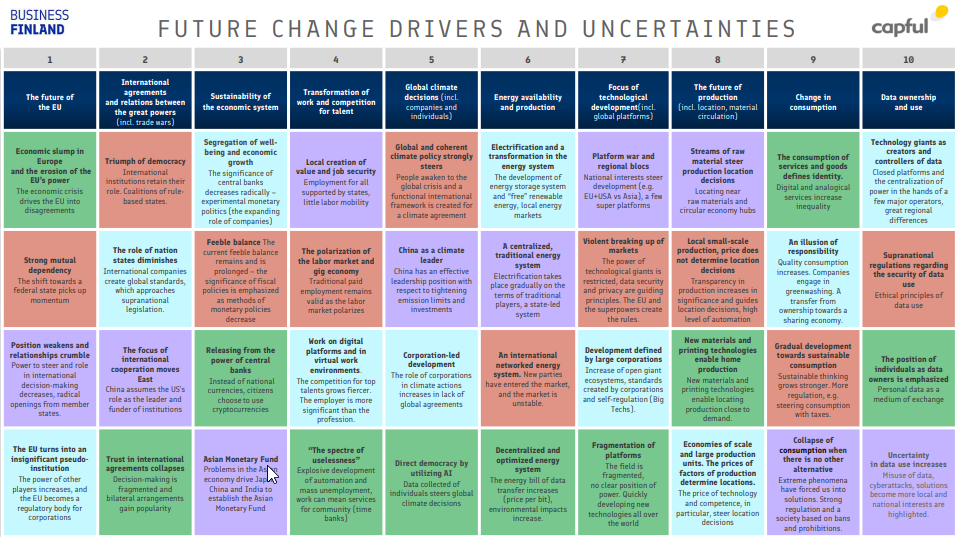

For example, Business Finland – the Finnish government organization for innovation funding and trade, travel, and investment promotion – identified ten uncertainties in its scenario work. The work aimed at envisioning alternative futures of Finland’s competitiveness with key uncertainties arising from the sources of macro change mentioned above: the future of the EU, the sustainability of the economic system, the future of production, and data ownership and use, to name a few.

Image credit: Business Finland

Image credit: Business Finland

These uncertainties are important not only for governmental organizations to explore – but they're also relevant for many types of companies doing business in and outside of Finland as they concern some of the major shifts in the broader operating environment.

Step 2: Imagine alternative outcomes for the uncertainties

Since "I don't know" is often the first answer to how an uncertainty will develop, we need to start imagining and entertaining alternative outcomes for the uncertainties.

There are two options for this:

Option 1: Dichotomies

In this option, you envision two opposite outcomes for each uncertainty (i.e., yes/no, sooner/later, more/less, etc.). To answer the question of what will the world look like in 2050, professional services firm Arup looked at two key uncertainties with two opposite outcomes to produce four plausible futures:

- Planetary health: improves versus declines

- Societal condition: improves versus declines

Option 2: Pluralism

In this option, you envision multiple alternative outcomes (e.g., three to four) for each uncertainty. It's often easy to think of three alternatives – the pessimistic, the neutral, and the optimistic – but what about a fourth alternative? Remember that one part of the scenario work is to stretch our thinking. Don't stop at three alternatives – think about that fourth one as well.

As Director of Strategy at Lindström, one of Europe's leading textile service companies, I've helped the company build COVID-19 exit scenarios with the following uncertainties, each with three alternative outcomes:

- Vaccinations

- Government responses

- Consumer behavior

- Sustainability

- Technology & work

- Economic recovery

The timeframe of your scenarios naturally determines the potential outcomes of the uncertainties or drivers of change. Often, we think of scenarios as a tool for long-term foresight, but they can also be used to support shorter-term decision-making. In these turbulent times, it is more fruitful to think in months, or even days, than years.

Step 3: Prioritizing and selecting uncertainties for the scenarios

After imagining the alternative outcomes for your uncertainties, the next step is to prioritize and choose which one to bring into the scenarios.

Again, we can consider two options.

Option 1: 2 uncertainties

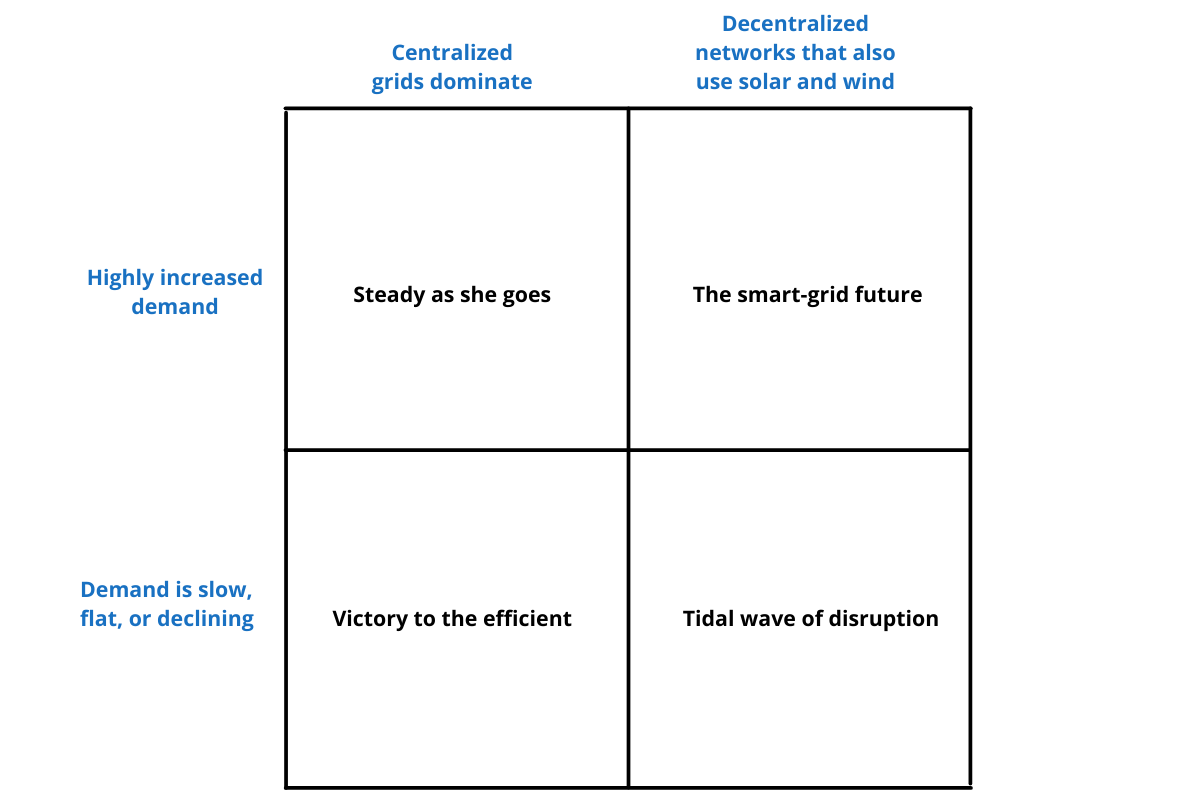

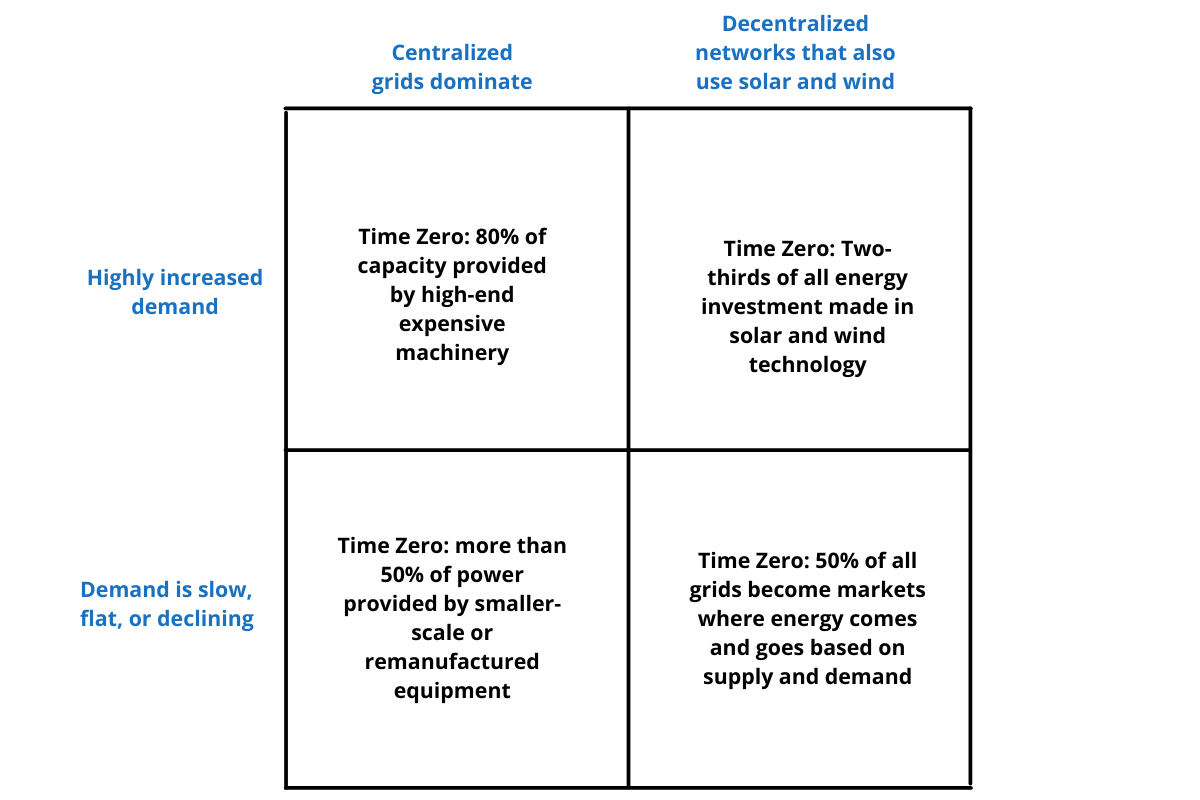

This option prioritizes two uncertainties that often have contradictory outcomes. As you can imagine, this option produces a 2x2 matrix of four different scenarios. For example, for an energy company, the uncertainties and alternative outcomes could be: 1) centralized grids dominate versus decentralized networks that also use solar and wind, and 2) highly increased demand versus demand slow, flat, or declining, leading to four different scenarios:

- Steady as she goes: centralized grid dominates; highly increased demand

- The smart-grid future: decentralized networks that also use solar and wind; highly increased demand

- Victory to the efficient: centralized grid dominates; demand slow, flat, or declining

- Tidal wave of disruption: decentralized networks that also use solar and wind; demand slow, flat, or declining

Option 2: Multiple uncertainties

This option prioritizes multiple uncertainties and often multiple alternative outcomes for those uncertainties. The multiple uncertainties option produces a lot more combinations for potential scenarios than Option 1. If there are ten uncertainties with four alternative outcomes for each, there will be 1,048,576 potential scenarios. To narrow down the number of possible scenarios, we can do a few things:

- First, we can check for the consistencies of the alternative outcomes for the uncertainties in pairs: given the scenarios' timeframes, is it plausible to think that Outcome A for Uncertainty 1 would happen around the same time as Outcome B for Uncertainty 2? A simple yes or no could suffice, or we might want to go to a more detailed scale (e.g., 0 to 5, from strongly inconsistent to strongly consistent). Removing inconsistent pairs of outcomes reduces the number of potential scenarios.

- Second, we can identify results that would be the same from one possible scenario to another and eliminate those. For example, with four uncertainties, we might want to remove scenarios with the same alternative outcome for three uncertainties.

Overall, Step 3 should lead to a small preliminary selection of different scenarios. These scenarios should differ from each other – one more desirable than the other, one more undesirable than the other, one more likely than the other, one more unlikely than the other, and so on.

Step 4: Attaching clever names to scenario candidates

Now that we have the scenarios' skeletons, it's time to start giving them catchy names. What would you call a future where your selected uncertainties and outcomes would happen? Would it be titled “tidal wave of disruption,” as was the name of one of the scenarios presented earlier, or something else? Jim Dator’s four generic futures – continuation (business as usual/growth), discipline (order and control), collapse (systemic breakdown), and transformation (high-spirit) – are a source of inspiration for naming scenarios. Respectfully, award-winning futurist Leah Zaidi titled four generic futures for the world after COVID-19 as Detour Back; Keep Calm, Carry on; Vicious Circles; and We, Not Me.

Alternatively, film titles or historical events could serve the purpose of making scenarios interesting and memorable. Overall, naming scenarios is not a trivial exercise, and hence, it should be considered as an individual step in the process. The usefulness of scenarios depends on them being easily memorable, especially in times of decision-making. When scenarios have a catchy name, they are more likely to become part of an organization’s vocabulary, pop up in discussions where needed, and provide a focus for describing and monitoring their development.

Step 5: Describe the development paths leading to alternative futures

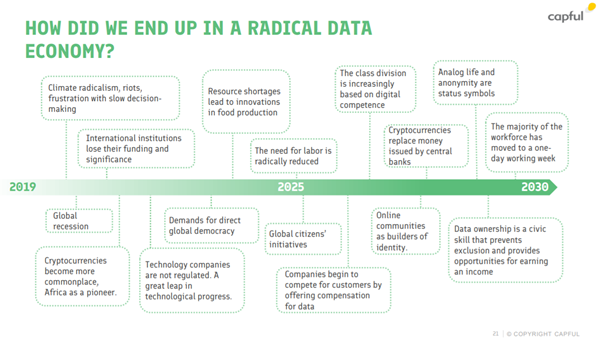

Throughout steps 1 through 4, you have created and selected the building blocks of scenarios: the key uncertainties, their outcomes, and titles of the scenarios. You now have a rough idea of how the future might look. For example, going back to the Business Finland scenarios mentioned above, a scenario titled "Data Saves and Enslaves" could be built upon three uncertainties and the following outcomes:

- Global climate decisions: global movements call for climate action

- Focus of technological development: no regulation, rapid progress of AI and automation

- International agreements and relations between the great powers: fragmentation and AI in decision-making

Then, to describe the development path to the scenario, a logical and plausible timeline of events could be compiled. Below is an example of the scenario titled Data Saves and Enslaves with a 10-year timeline: what events would leave us ending up in a radical data economy?

Image credit: Business Finland

Image credit: Business Finland

A few techniques are useful to build such a timeline, including backcasting and identification of inflection points.

Backcasting is a method to plan the actions or events that could lead to the future envisioned. As the name implies, it’s about working backward from the future to the current state. When reverse-engineering the vision, the following questions help:

- What needs to happen in Year X so that the future would be as envisioned in Year Y? What should we do, what should our stakeholders do, what should happen in the regulation, etc.?

- Who are the stakeholders that have an influence on us, and who do we need to influence for a particular scenario to happen? Who would find the scenario desirable? Who wouldn't? Who do we need to win on our side?

- What risks/opportunities are present in Year X that can impact the future envisioned in Year Y?

Identification of inflection points: an inflection point is a moment in time that signals a scenario is most likely to happen. One might call these inflection points “Time Zero Events.” Coming back to the scenario example from the energy industry (taken from Rita McGrath’s latest book), inflection points could look something like this:

Identification of the inflection points and backcasting also work nicely together. Once you identify an inflection point, you could backcast from it to map out the events that would lead to the inflection point happening. For example, if the inflection point was that two-thirds of all energy investments are made in solar and wind technology, what would need to happen six, 12, and 18 months before the inflection point? Try formulating these events as news headlines to help spark your imagination.

Step 6: Assess and prioritize choices and decisions against the scenarios

In addition to using scenarios to describe development paths to alternative futures, you can also use them to assess and prioritize choices and decisions against the scenarios. Scenarios – alternative views of the future – can support the timing of the choices and efforts needed for those choices to succeed. For example, creating scenarios around the adoption of electric vehicles (slow to rapid) can support companies in the electric mobility industry in deciding when and how much to invest in development and prepare for the possible changes in the pace of adoption early on.

Choices can be assessed in different scenarios with the following questions:

- Is the decision or action good, bad, or neutral in a scenario?

- Would the decision or action impact the likelihood of the scenario happening?

When considering the prioritization of choices, categorizing them in the following way helps in distinguishing between different types of decisions:

- Required moves: actions or choices that must be taken regardless of the scenario to ensure that the organization will stay viable in the near term

- No-regret moves: actions or choices that make sense under any scenario

- Big bets: actions (e.g., investments) or choices made with the expectation that a desirable scenario would emerge

- Contingent moves: actions or choices whose success depends on a scenario to emerge

- Options: actions or choices that are the first steps or experiments in a scenario and that can be scaled when moving forward

Scenario planning brings the greatest benefits when done continuously. Make the most out of the scenarios by frequently updating the development paths and following how the uncertainties, inflection points, and other indicators develop. Sometimes, the scenarios might need a complete overhaul. Monitor the plausibility of the scenarios and reassess and reprioritize the choices and actions.

For strategy or innovation management, scenarios offer a great tool to test and validate the organization's future direction. For example, with R&D, are we on the right track, and will we be relevant in the future?

So, now you know the process for scenario planning and how to prep your organization for the future. "I don't know" is no longer your go-to answer to how uncertainty will develop. Feel free to share how your scenario-planning process is going in the comments below.

--

For software support, check out HYPE Strategy- Discover the gaps in your strategy and identify the trends, technologies, and organizations that can fill them.