Whether in pursuit of innovation or simply to keep on course, planning for change is an essential skill all organizations should master.

The concept of change management, as both a topic and a business model, dates back to the early 1950s. Here, we examine the work of some of the key academics and practitioners in this field, including Kurt Lewin, a German-born American social psychologist who pioneered "force field analysis" and developed a related three-step change management model.

What is planned change?

Planned change is the process of preparing an entire organization, or a significant part of it, to achieve new goals or move in a new direction. This direction can refer to a company’s culture, internal structure, processes, metrics and rewards, or any other aspect related to the business.

While constant change is the new normal and the best companies embrace it, not all change is planned. On occasion, organizations will suddenly have to adapt to new market demands, unexpected market shifts or heightened competition.

It’s also worth noting that planning for change and planning for innovation are not the same. Some practitioners describe planning for change in general as incidental, administrative, and serving mostly "cosmetic purposes." The role of this type of change is, therefore, to maintain stability and incorporate certainties into the organization.

By contrast, innovation is a transformative process that requires deeper change (a makeover), customized tools, and creativity. Innovation, as a change process, can therefore appear unexpected and even nonsensical.

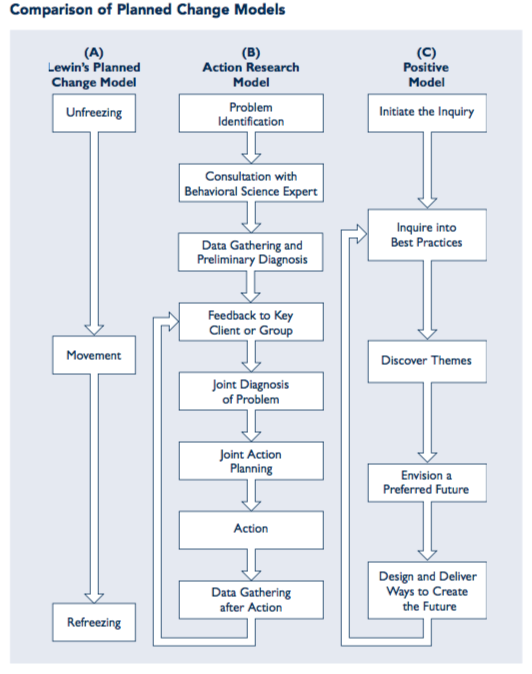

A comparison of planned change models

Experts in organizational development and change often refer to three well-established models:

- Kurt Lewin’s three-step model

- The “action research” model, popular in development work

- The “positive model”, with a unique focus on sufficiency rather than deficit

Source: Cummings and Worley (2008)

Source: Cummings and Worley (2008)

Three-step change model

Lewin’s change model provides a general framework for planned change, and includes three basic steps:

-

Unfreezing

Reducing the forces that keep things within an organization the way they are. In Lewin’s model, unfreezing occurs through so-called "psychological disconfirmation", for example, running an organization-wide innovation survey and evaluating the results. -

Moving

Shifting an organization’s behavior, which involves some kind of intervention. -

Refreezing

Stabilizing an organization in a new state of equilibrium. This step isn’t possible without support mechanisms, for example, building a solid corporate innovation capability.

Lewin’s model (1951) originates from “force field analysis” (or the “force field model”), a method of understanding change processes in organizations. In force field analysis, change-related problems are characterized by an imbalance between so-called driving forces – such as new personnel, changing markets, or new technology – and restraining forces – such as fear of failure, “not invented here” syndrome, or organizational inertia.

To thrive, an organization must unfreeze the driving and restraining forces, introduce an imbalance (increase the drivers, reduce the restraints – or both), and, finally, refreeze the forces. This final step brings an organization back into "quasi-equilibrium."

Because the three steps of Lewin’s change model are relatively broad, considerable effort has gone into elaborating them.

Action research model

One of the examples is Kotter’s (1996) eight-stage model, which refers to establishing a sense of urgency; creating a guiding coalition; developing a vision and strategy; and communicating the change vision (unfreezing). The remaining stages include empowering broad-based action; generating short-term wins (moving); consolidating gains and producing more change; and anchoring new approaches in the culture (refreezing).

Also known as participatory action research, action learning, action science, and a self-design model, the action research model is popular among organizational change specialists. Action research activities are typically top-down and happen in iterative cycles of research and action. Consequently, they require considerable collaboration between staff and external stakeholders.

Other important features of the model include:

- Strong emphasis on data gathering and diagnosis before action and planning – e.g., using big data to solve (big) problems

- Used to enact change at the department level and even the organizational level; it is also a popular model in developing nations (applied to international settings)

- Used to promote social change and innovation

The eight key steps in the action research model:

- Problem identification (typically by an executive)

- Consultation with behavioral science experts

- Data gathering (interviews, observation, questionnaires, performance data) and preliminary diagnosis

- Feedback to key stakeholder group

- Joint diagnosis of a problem

- Joint action planning

- Action (the actual "moving" from one state to another)

- Data gathering after action (often leads to re-diagnosis and new action)

The positive model

The third planned change management model is the positive model. This model is a notable departure from both Lewin’s model and action research model. While the latter two models are deficit-based (focusing on problems and scarcity), the positive model focuses on what the organization is doing right and how existing capabilities can be used to help it reach new heights.

The positive model is also about:

- Positive expectations that create anticipation that directs behavior toward making things happen.

- Applying a process called appreciative inquiry. This process infuses a positive value orientation into analyzing and changing organizations.

- Promoting member involvement and creating a shared vision; the shared appreciation acts as a guide to what the organization could aspire to.

The five key steps in the positive model:

- Initiating the inquiry – i.e., the issues the organization has the most energy to address.

- Inquiring into existing best practices – through members of the organization conducting interviews

- Telling "innovation stories"

- Discovering the themes or commonality of peoples’ experiences

- Envisioning the preferred future via “possibility propositions” and relevant stakeholders, and delivering ways to create the future ("the action" itself)

Challenging planned change management

While we can learn a lot from the three planned change models and their variants, they do have some shortcomings:

- First, the models look at change as a linear process. In reality, however, linearity is the exception rather than the norm. Often, change managers and innovation managers see overlaps between activities, which complicate their interventions.

- Second, change seldom happens in pre-determined steps. While a framework is useful, enacting organizational change requires a lot more information. In addition, steps can differ considerably across situations – not to mention industries.

- Third, because change is not a rationally controlled, ordered process, the models’ effectiveness is limited. An alternative way of looking at change is as a continuum of incremental changes (fine-tuning) and fundamental changes that alter how an organization operates (business model changes for example) – holacracy is one such approach.

Takeaways

Planned change models are a means to an end, not ends in themselves. To survive and thrive, organizations and experts must consider a variety of variables including timing, partnerships, and tools. In the words of Jack Welch, former CEO of General Electric:

"Change, before you have to."

And if you’d like help with planning and managing change, reach out to our team of innovation experts and we’ll help you to navigate your change journey.