In an older post from February I argued that creativity had become a prevailing buzzword in the business literature and that, despite conflicting definitions, its strategic importance was hard to deny – chiefly in helping entities, large and small, survive.

Another trendy word with similar implications is ambidexterity. Not the property of being equally skillful with both hands, of course, but the organizational ambidexterity defined as the ability to pursue two disparate things at the same time; things like: efficiency vs. flexibility, exploitation vs. exploration, stability vs. adaptability or even short-term profit vs. long-term growth (source: FT’s Lexicon).

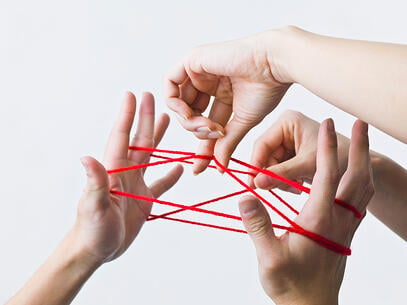

To use a visual metaphor, imagine a set of corporate hands looping strings to create figures – “Soldier's Bed”, “Candles”, “Diamonds” or “Clock”. Yes, you’ve guessed it: playing organizational ambidexterity is in many ways like playing string games i.e. Cat’s cradle. It takes mastery of the old patterns, curiosity for the new, teamwork and above all, practice.

Published in June 2013, Organizational Ambidexterity: Past, Present and Future offers by all accounts the most comprehensive summary & review of existing topic-related research to date. In this insightful piece, authors Charles O’Reilly of Stanford University’s Graduate School of Business and Michael Tushman of the Harvard Business School explore the known and the yet-to-be-known aspects of ambidexterity, and provide personal recommendations in the conclusion. In as follows are some takeaways from their impressive work.

Origins and Context

Every organization is unique. Unique in terms of its internal structure, its external environment and above all: its strategy. For example, firms operating in stable settings tend to develop mechanistic management systems (clear hierarchical relations, well-defined roles) while firms operating in more unstable environments lean towards organic ones (less reliance on formalization and specialization). To succeed over longer periods of time and avoid becoming irrelevant in the marketplace however, adjustments of these default (operating) modes are preferred. Irrespective of history, industry, or current scenario, survival becomes a paradox of administration: how to exploit existing assets and provide sufficient room for exploration too? Enter ambidexterity.

The first use of the term was by Robert Duncan in 1976; his definition read: the need to shift structures to initiate and in turn, execute innovation. The link to firm survival arrived two decades later – in 1996 – when Tushman and O’Reilley suggested an alternative: the ability to simultaneously pursue both incremental and discontinuous innovation […] from hosting multiple contradictory structures, processes, and cultures within the same firm.

Today, two decades later, the research questions are still pouring: Is ambidexterity truly linked to firm survival? Is it accomplished through architecturally separate units? Under what conditions is ambidexterity most useful etc., making it difficult to recall the original, unblurred meaning.

What the Current Evidence Shows

By and large, ambidexterity is positively related to constructs like sales growth, innovation, market valuation, and, as previously seen, survival - though it can, under certain circumstances, prove duplicative and inefficient too. Furthermore, it works best when the firm is pressured by increased competitiveness and when its resource levels are high. Case-studies describing these complexities include: Smith Corona, Olivetti, HP, Polaroid and IBM.

How does ambidexterity unfold in practice? One theory suggests it takes place in a sequential fashion through the shifting of structures over time. Subsequent theories outlined a simultaneous/ structural fashion or autonomous explore and exploit units, structurally separated from one another. Finally, a 3rd approach surfaced: the so-called contextual ambidexterity, which encouraged individuals to make their own judgements and divide their time between demands for alignment and adaptability.

As to their unique strong points, each of the three theories works better in a different setting. The sequential approach, for instance, is better suited for slower moving sectors such as the service industries. Likewise, a good illustration of contextual ambidexterity is the account of how the Toyota production system operates: workers perform both routine tasks like automobile assembly (exploitation) but are also expected to continuously change their jobs to become more efficient (exploration).

Back to the Future and Conclusions

The central message of Tushman and O’Reilly’s review is clear: unless vague definitions are abandoned, ambidexterity - as a research topic - will continue to dilute. In other words, applying the term too broadly can lead to dangerous distancing from the original phenomenon, and pave the way for unhelpful, even misleading advice for firms. In addition, more nuanced questions about how ambidexterity works in practice will require more in-depth case studies; more investigation is needed to determine the particularities of firms that flourish with ambidexterity, and of those that flop. Finally, with the locus of innovation expected to shift to the communities, studying phenomena at the eco-system level, instead of the firm level, becomes another promising area for further research.

On a personal note, Tushman and O’Reilly conclude: In our view, organizational ambidexterity is about survival: how IBM has moved from a maker of hardware to software to services, […] how the Hearst Corporation has moved from a publisher of newspapers to being a provider of data, or how Fuji has moved from a maker of photographic film to a provider of fine chemicals. It is about why great companies like Polaroid, Kodak, and Smith-Corona have failed to make these transitions. This is both a topic of immense practical importance and great theoretical opportunity.