I was recently asked a very down-to-earth question: "Where do you find answers to practical issues in innovation management?" To this, I'd normally reply "forums, journals and HBR." They're all sources I recommend regularly. This time, however, and to the amusement of the innovation manager asking, the word "Netflix" came out first. No, not the company – although they are setting new standards in the business world. I meant an actual Netflix show.

You see, Las Chicas Del Cable (Cable Girls), a telenovela set in 1920s Madrid at a time when a national telephone company opened its headquarters in the city center, has a lot to teach us about the next practical issue in innovation management that I'd like to address. Namely: identifying stakeholders in a project/collaboration.

In the show, four young female operators manage romance, friendship, and the modern workplace to pursue their dreams and seek independence. They also identify and manage their stakeholders carefully and creatively as the invention of the rotary dial (a component of the modern telephone) puts their jobs at risk. So, what can the operators' experience teach innovation managers about the process of finding and labeling stakeholders? What is there to learn?

Before we get to the learnings, let's look more closely at the problem.

No company is alien to the concept of a stakeholder. Fictitious ones included. Stakeholders are, after all, practically everywhere. And their numbers and varieties continue to grow thanks to globalization. Whether primary or secondary collaborators, owners or non-owners of the business, actors or those acted upon, in a voluntary or non-voluntary relationship with a firm – each of these categories can potentially have something at “stake.” That is, each of them can affect or be, in turn, affected by the achievement of an organization's/innovation project's objectives.

Considering the above, identifying the right stakeholders for each innovation project and managing those relationships accordingly is key to success. But who determines if a stakeholder is important? And where should managers start?

While there are many indications of (and even frameworks to help identify) who or what represents a potential stakeholder, not all of them are valuable. To help shed some light on this theme, I've revisited an old, but still relevant article. In a 1997 contribution to the Academy of Management Review, Ronald Mitchell, Bradley Agle, and Donna Wood discussed stakeholder identification and salience and defined who and what really counts. A summary of the ideas in this article is right below.

Determining your stakeholders and what's at stake

What constitutes a stakeholder? It depends. If you're a well-known comedian like Jerry Seinfeld, it might be the fans, the movie studios and production companies he works with, the car dealerships he collaborates with, his family, or his friends. If you're a supplier of drinking water, however, it might be everyone from the individuals and organizations you supply water to (the direct customers) right down to the environment.

The very first (recorded) use of the term "stakeholder" can be traced back to an internal memo at the Stanford Research Institute in 1963. The memo defined stakeholders as the groups on which the organization was dependent on for its survival. In 1984, Edward Freedman elaborated on this definition by noting that stakeholders are "any group or individual who can affect or is affected by the achievement of the organization's objectives."

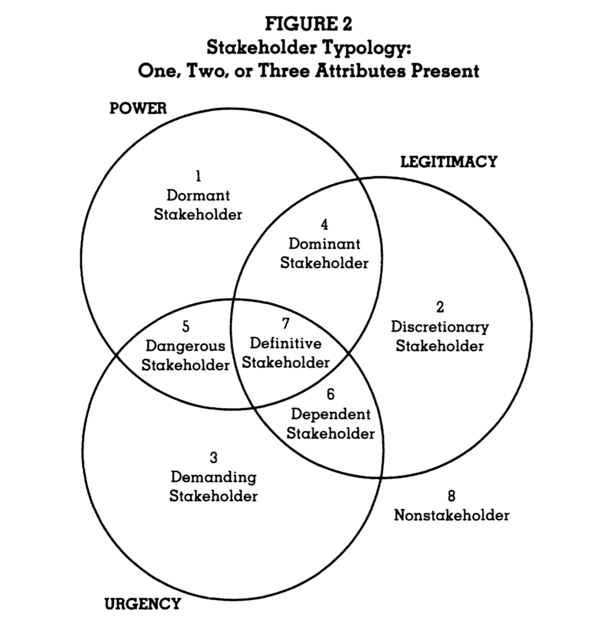

While both definitions were useful, they remained broad. Consequently, follow-up studies like that of Mitchell, Agle, and Wood suggested frameworks to help define, identify, and classify stakeholders more effectively. One framework leveraged three attributes a potential stakeholder might or not have:

- The power to influence the firm.

- The legitimacy of the relationship with the firm.

- The urgency of the (stakeholder's) claim on the firm.

We'll get back to these categories (and possible combinations between them) in a bit.

Unlike prior definitions and classifications, Mitchell, Agle, and Wood's approach was dynamic and provided plenty of nuances. By looking at three different attributes, in isolation as well as in combination, it became more apparent how managers could prioritize relationships and what decisions they should take to manage them. Hence, the value of this research for modern innovation managers, too.

But what about the stake? Just like stakeholders, the notion of a "stake" also has its nuances. The stake generally represents the interest the stakeholder has in the firm/project and vice-versa. This means the stake can be classified as unidirectional or bi-directional – when both stakeholder and firm bear some risk. This stake can also be with or without the two parties' knowledge or consent. For example, practically all of humanity has a stake in the success of the SpaceX mission – but not everyone knows it. Similarly, in a large development project, the wildlife population in the area has a stake – but without its consent.

In the conversation about the stake and what exactly is at stake, the element of risk is, in fact, the most important. Without an element of risk, there is no stake. This means some stakeholders can be pure claimants (they have a claim) or influencers (they can influence). Stakeholders can also be in a potential or an actual relationship with the firm. Finally, there can also be a difference in dependency. For example, when an organization and a stakeholder are in a relationship, one of the two can dominate, or there can be a mutual power-dependence.

Reading tip: The Stanford Social Innovation Review is a great place to learn about how organizations can better cater to the needs of their partners.

How stakeholder attributes are defined and combined

Now that we've looked at some of the nuances of stakeholders and stakes let's get back to the classification.

As Mitchell, Agle, and Wood explain in their article, power, legitimacy, and urgency will collectively determine what type of stakeholder (if any) a manager and his/her organization are dealing with. In the absence of any of these attributes, the entity is probably a non-stakeholder.

According to the authors, power refers to how probable an entity is to carry out their will despite resistance. While the term is difficult to define, it is easy to recognize – especially by stakeholder relations departments or similar structures in firms.

Legitimacy refers to whether something is at risk to the potential stakeholder (property rights, moral claims, etc.). Legitimacy and power are distinct attributes, but, when combined, they create authority (like the EU Commission's authority in fining Google).

Finally, urgency refers to whether the relationship with the potential stakeholder is time-sensitive and critical to the stakeholder.

Power, legitimacy, and urgency are not steady states, however. They tend to change over time and are not definitive. The existence of each attribute is, in fact, a matter of not one but multiple perceptions. In other words, several people in an organization will determine whether something or someone is a stakeholder and, if so, which of the three attributes they possess.

The 7 stakeholder classes

Source: Mitchell, Agle, and Wood (1997)

For (innovation) managers to achieve desired ends, they must pay attention to various stakeholder classes connected to their projects. By considering how much power, legitimacy, and urgency each stakeholder has, they can be assigned to a category and given a certain priority.

These categories are: dormant, discretionary and demanding (the so-called latent stakeholders), dominant, dangerous and dependent (or expectant stakeholders), and definitive stakeholders. An individual or firm that is not part of any of these categories it probably a non-stakeholder. Let's take them one by one.

1. Latent stakeholders

The first category is latent stakeholders. Latent stakeholders are a category that possesses only one of the three attributes (power, legitimacy, and urgency), and managers often choose to ignore them.

Latent stakeholders that possess only power are called dormant. But having power does not always mean using it. An example includes stakeholders that can potentially invest a lot of money into the project, like wealthy individuals or banks, or that While tricky, it is sometimes possible to predict which of these stakeholders will act, depending on public causes/concerns.

Latent stakeholders that possess legitimacy are called discretionary. They do not have the power to influence the firm and have no urgent claims. Non-profit organizations such as schools and hospitals that receive donations and volunteer labor fall into this category. Here is a list of surprising pairs of corporations and non-profits that illustrate this well. For example, Hanes matches customer purchases with donations to The Salvation Army for people that cannot afford to buy new clothes.

Finally, latent stakeholders that possess legitimacy, but none of the other two attributes, are called demanding. It could be a lone protester who is usually dismissed by managers despite his demands, like this half-naked picketer that demanded summer in front of Moscow's main meteorology center.

2. Expectant stakeholders

The second category includes expectant stakeholders – or the stakeholders that possess any two of the three attributes and therefore "expect" something from the organization. Having two attributes is also a signal of a stakeholder being "active" rather than passive.

Powerful and legitimate stakeholders are called dominant. These stakeholders will typically have some formal mechanism in place to help them act. Corporate boards are a case in point because they include representatives of owners, creditors, and community leaders. If this is the case, an organization might have an investor relations department to manage this group.

Stakeholders with urgent and legitimate claims are called dependent. In the case of an oil spill, various groups might have urgent and legitimate claims but will lack the formal power to impose them.

Finally, urgency and power can combine to create dangerous stakeholders. For example, environmentalists spiking trees to avoid cutting it down, or shootings (for example, the YouTube incident) to "make a point." Identifying this last category is particularly important to mitigate risk and possibly even save lives. While dependent and dangerous stakeholders are not typical for a standard innovation project, they are worth considering nevertheless – especially in a case in which the firm is part of, and innovates with, a larger ecosystem of partners.

3. Definitive stakeholders

The third category that combines all the categories in the framework signals definitive stakeholders. Stakeholders that see their stocks plummet and act upon this, for instance, fall into this category. Initially possessing only power and legitimacy, the sense of urgency instilled by the news can prove dangerous for an organization. (Here's a nice read about The Art of Selling a Losing Position)

Conclusion

Summing up, power, legitimacy, and urgency are three important attributes that innovation managers can use to categorize their stakeholders and then decide what actions to take.

While the framework suggested by Mitchell, Agle, and Wood is useful and informative, it is by no means the only one. Practice shows us that identifying and managing stakeholder groups all comes down to managers' experience and perceptions. Being prepared to be held "accountable" for the progress and outcomes – for better and for worse – of the innovation project is a sure, straight-forward way to keep everyone happy. Especially the expectant stakeholders in the Board.

|

Notes and further reading: "Toward a Theory of Stakeholder Identification and Salience: Defining the Principle of Who and What Really Counts" by Ronald K. Mitchell, Bradley R. Agle, and Donna J. Wood is the article summarized in this blog post. |