There are a variety of forces impacting colleges and universities today: economic and demographic, financial and ideological. Even forces related to how higher education is “consumed.” In response to this fast-changing environment, institutions in higher education are changing, too.

For example, institutions are finding new ways of teaching as well as new ways of conducting and disseminating their research. The flipped classroom model and the “de-centring of the professor” trend on the one hand, and ResearchGate (networking platform), The Academy of Management Discoveries (innovative journal), and special innovation programs on the other hand, are great examples as such.

To maintain their relevance in the long run, however, organizations in higher education must go beyond tweaking their core competencies (teaching and research). Instead, institutions must build entirely new ones (engagement/relationship building).

But don’t take my word for it.

Recommendations like these span from a growing body of research designed to understand how the higher education industry is changing and how best to orchestrate that change.

One great example is a comprehensive report written by LSE Enterprise, the commercial arm of the London School of Economics and Political Science, and Panteia, an independent research institute for the European Commission in 2014. The report sums up well the current challenges for higher education and argues that adopting a “system” view can help organizations – as well as their stakeholders – see the big picture and fine-tune their innovation efforts accordingly. Below, a few takeaways from this interesting work.

Current challenges

Like all industries, education is influenced by forces in its external environment. According to the LSE report, institutions in higher education today face three broad categories of challenges: globalization, supply and demand, and funding.

In the wake of globalization, colleges and universities are met with changing standards for excellence and increased competition. Additionally, cross-border operations – e.g., having campuses across multiple geographies, and the mobility of students and staff, call for adjustments to existing operating models.

On the supply/demand side, new teaching and learning technologies – i.e., Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) and blended learning, analytics and databases, as well as students’ changing financial circumstances and changing expectations from an education facility are calling for deep reform.

Finally, funding issues such as the changing balance between an individual’s contribution to the costs of higher education and public funding is creating friction.

These three categories challenge and often impair an institution's ability to innovate and deliver the best results. So, how do colleges and universities cope? The answer, according to the report, lies in the perspective taken.

The 'system' view

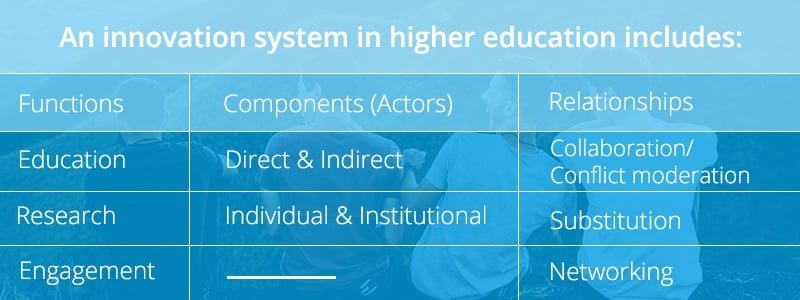

At a high abstraction level, higher education can be viewed as a set of inter-related functions, components, and relationships. Essentially, a system.

Source: LSE Report

The functions of this system include: education, research, and engagement (or relationship building), whereas the components (or actors) are direct and indirect as well as institutional and individual.

As for the relationships between these functions and actors, one can distinguish between: collaboration and conflict moderation, substitution, and networking. Collaboration/conflict moderation can be triggered, for example, by the introduction of an innovation that creates a divide between senior and junior staff (e.g., using augmented reality in the classroom).

Substitution refers to one actor taking the lead on a function traditionally belonging to another (e.g., a university, decides to complement its activities in teaching and research with technology transfer and firm formation).

Finally, networking refers to an “aggregation” of partners as is especially important for a research project's sustainability (e.g., the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) and its extended ecosystem of partners). Networking allows institutions to build a reputation, while its staff benefits from peer learning, knowledge sharing, and testing ideas. Not surprisingly, research networks in academia are comparable to “joint ventures,” the report finds, and are therefore critical to an institution’s success.

Of all three elements of a system, relationships are perhaps the most important. Relationships, after all, determine how innovation is diffused among the partners – e.g., universities, for-profit organizations, government, etc., and how this information is used.

|

Reading tip: |

The system view has two important advantages according to the report. First, it allows researchers to analyse the impact of innovation on the individual elements of the system – e.g. for-profit colleges, non-profit organization, universities, agencies etc. Secondly, it provides a dynamic view of higher education (as a whole) by considering the interaction between the various functions, components and relationships. In this way, some interesting dynamics – and dilemmas – emerge.

Key dynamics and organizing for success

As mentioned above, looking at higher education through the “system” lens reveals several important dynamics. By analyzing these dynamics carefully, innovation managers in higher education can focus their efforts where they are needed and ultimately do better informed decision-making. Today, three important trends (dynamics) affecting higher education include:

- Inadequate management of the innovation process

While management theory and tools are part of university curriculums, university managers are not trained to apply them. Moreover, the staff tasked to promote innovation in higher education are actually promoted academics instead of seasoned innovation professionals. - The “spiral of change”

As the elements of a higher education system become more aligned, this facilitates the success of innovation and transformation initiatives; successful innovation, in turn, strengthens the system and leads to more ambitious projects, better partner selection etc,. - Innovation in higher education is typically slow and incremental

instead of disrupting teaching, research, or networking entirely, innovation tends to provide new ways of doing traditional tasks.

|

Reading tip: |

In light of these dynamics, the report outlines a few recommendations for institutions in higher education. To stay relevant and sustainable, institutions must consider:

- Nurturing an innovation culture; a culture that “enhances creativity, creates awareness of the benefits resulting from the implementation of the innovation, stimulates openness to innovation, and minimizes resistance to change”

- Adequate incentives and rewards for members of staff who engage in innovation

- Engaging their staff to explore new learning technologies

- The use of cross-institutional collaboration

- Adequate measures for the skills development of teaching staff

- Reviewing organizational boundaries and linkages

Summing up…

The complex higher education system contains rich opportunity for innovation but also for failure. To succeed, institutions must understand their environment, their partners, and the links between them. Additionally, institutions must be proactive and anticipate the impact of globalization, supply/demand in higher education, as well as funding issues.

As Ryan Craig’s article on VentureBeat notes: “most colleges and universities today provide the educational equivalent of enterprise software.” Whereas to change, colleges and universities need to migrate towards customizability, friendly pricing, and innovative delivery models. In an ideal world, we would see “Education-as-a-service” becoming mainstream and institutions reaping the benefits of a lean operating model. Whether this recommendation, or the one outline by the LSE report will catch on remains a matter of policy and ultimately faith in innovation.

Looking for advice on innovation in higher education? Learn more here.